Heme

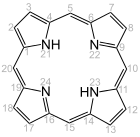

Heme or haem is a coordination complex 'consisting of an iron ion coordinated to a porphyrin acting as a tetradentate ligand, and to one or two axial ligands.' The definition is loose, and many depictions omit the axial ligands. Many porphyrin-containing metalloproteins have heme as their prosthetic group; these are known as hemoproteins. Hemes are most commonly recognized as components of hemoglobin, the red pigment in blood, but are also found in a number of other biologically important hemoproteins such as myoglobin, cytochromes, catalases, heme peroxidase, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Heme or haem is a coordination complex 'consisting of an iron ion coordinated to a porphyrin acting as a tetradentate ligand, and to one or two axial ligands.' The definition is loose, and many depictions omit the axial ligands. Many porphyrin-containing metalloproteins have heme as their prosthetic group; these are known as hemoproteins. Hemes are most commonly recognized as components of hemoglobin, the red pigment in blood, but are also found in a number of other biologically important hemoproteins such as myoglobin, cytochromes, catalases, heme peroxidase, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. The word heme is derived from Greek αἷμα haima meaning 'blood'. Hemoproteins have diverse biological functions including the transportation of diatomic gases, chemical catalysis, diatomic gas detection, and electron transfer. The heme iron serves as a source or sink of electrons during electron transfer or redox chemistry. In peroxidase reactions, the porphyrin molecule also serves as an electron source. In the transportation or detection of diatomic gases, the gas binds to the heme iron. During the detection of diatomic gases, the binding of the gas ligand to the heme iron induces conformational changes in the surrounding protein. In general, diatomic gases only bind to the reduced heme, as ferrous Fe(II) while most peroxidases cycle between Fe(III) and Fe(IV) and hemeproteins involved in mitochondrial redox, oxidation-reduction, cycle between Fe(II) and Fe(III). It has been speculated that the original evolutionary function of hemoproteins was electron transfer in primitive sulfur-based photosynthesis pathways in ancestral cyanobacteria-like organisms before the appearance of molecular oxygen. Hemoproteins achieve their remarkable functional diversity by modifying the environment of the heme macrocycle within the protein matrix. For example, the ability of hemoglobin to effectively deliver oxygen to tissues is due to specific amino acid residues located near the heme molecule. Hemoglobin reversibly binds to oxygen in the lungs when the pH is high, and the carbon dioxide concentration is low. When the situation is reversed (low pH and high carbon dioxide concentrations), hemoglobin will release oxygen into the tissues. This phenomenon, which states that hemoglobin's oxygen binding affinity is inversely proportional to both acidity and concentration of carbon dioxide, is known as the Bohr effect. The molecular mechanism behind this effect is the steric organization of the globin chain; a histidine residue, located adjacent to the heme group, becomes positively charged under acidic conditions (which are caused by dissolved CO2 in working muscles, etc.), releasing oxygen from the heme group.